Construction claims specialist receives international recognition

Stefan Müller, managing director of the construction claims specialist company, GibConsult, is the first South African member of the international Institute of Construction Claims Practitioners (ICCP). Membership is only given to those construction claims professionals who have the necessary education, qualifications, experience and competence that meet this industry’s high standards. Stefan is a specialist in preventative claims management and preparation with more than 16 years of experience and has been supporting clients on different types of large esteemed projects in Brazil, Dubai, Lebanon, Qatar, all over Europe and Africa.

The primary goal of the ICCP is to create professional standards for its members so that they can gain recognition within the industry as qualified and experienced professionals who deal with construction claims.

Construction claims have become an integral part of the international construction industry. Dealing with these claims requires a significant amount of experience and expertise. “On average, all projects have a claim potential of approximately twenty percent of which fifty percent are recognised too late or not at all”, states Stefan Müller. “The level of claims administration applied impacts directly on the level of success in identifying and addressing the risks and chances inherent in any given project”, he adds. Claims managers that prepare or respond to claims have a well-established knowledge of construction methods and are knowledgeable in contract interpretation and contract law.

Various international professional bodies exist in the construction industry such as the ICE for civil engineers (SAICE) and CESA for civil engineering companies, the Project Management Institute for project managers, RICS for chartered surveyors, RIBI for Architects and Quantity Surveyors International. The Institute of Construction Claims Practitioners’ goals specifically are to give recognition to construction claims specialists but also to establish and develop international standards for the management of claims. (www.instituteccp.com/)

By Annette Muller

•

June 11, 2021

Software can only interpret data which it is given. If this data is inaccurate the outcome will be inaccurate. This is when things become “hard on the software” , writes Stefan Müller. The software implemented supports the project from the early tender stage right through to the project wrap. The information gained over the period of the project can be evaluated and a “lesson learned” report generated to be taken into consideration for future projects. This is the way that software is marketed generally and is also purchased for projects. Reality, however, shows a slightly different picture, in that software still depends on external inputs which need to be delivered by the operator. Different sections of a project need different types of software varying from time management (scheduling) to commercial management (accounting) and lastly document management (data). In general, the time management software and distribution can be considered the more efficient of the three as there is very little room for interpretation, with changes to design being well tracked. The interpretation and “influence” of software outcomes tend to occur more often with the time and cost effects of the project. When considering the present two well-known Medupi and Kusile power station projects, the issues that come to mind immediately is that the projects are behind schedule and cost more than allowed for in budget. Accurate and realistic time input Each contractor, when signing a contract on any project, is required to submit a time schedule clearly showing all activities and durations which will form the so-called “baseline” schedule. This schedule is generated using standard industry software usually also specified in the contract agreement. Once approved by the client the progress of the contractor will be monitored both by client and contractor, to ensure the milestones and completion can be achieved. In some cases, the baseline schedule is unrealistic and inaccurate, and despite this, the client still approves the schedule. Then, should delays occur, being able to demonstrate the effect of delays becomes difficult. This usually results in data being “interpreted” differently by both parties and in some cases may even result in on aggrieved party seeking recourse via the dispute process. Controlling costs The software will produce a “manipulated” result, not necessarily incorrect or false but would not stand up against forensic analysis. As any computer literate person knows, any software program developed will stimulate the development of further analysis software tool to analyse the data from the original software program. This in turn, in most cases, can also be open to contradictory interpretation. Therefore, firstly the information used to compile the first project schedule (baseline) is to be as accurate and realistic as possible. Then the daily, weekly and monthly data must be accurately recorded and captured, so when a report is generated it will reflect the true progress of the project. As with the scheduling software, there are various acceptable cost controlling and accounting software packages. The contract agreement does not necessarily prescribe which software package to use, as this is left entirely to the contractor. The running costs of the project need to be accurately captured monthly in such a way that the daily costs can also be substantiated when needed. The actual costs should be attributed to a specific activity. When submitting the tender price, contractors are obliged to submit their pricing in a format supplied by the client. This format usually does not give sufficient breakdown of the actual costs and in claiming any additional costs there is an inherent difficulty in proving the actual costs of a delay. The hard facts are those that leave little room for interpretation. Once an event occurs where the contractor would be entitled to additional time and costs it is of paramount that this be substantiated by hard facts. These hard facts are based on the actual time taken to complete an activity; being able to show the actual costs makes it so much easier to compensate a contractor for any such occurrence. Hard facts Both the Medupi and Kusile power projects started without any of the parties paying attention to capturing and demonstrating “hard facts.” This has resulted in difficulties faced by all parties in terms of negotiating amicable settlement concerning the delays and additional costs that have occurred since the start of both projects. Bear in mind that projects of this magnitude in the international arena also have the same issues concerning time delays and additional unforeseen costs. This is also reflected in the increase and demand for qualified and experienced time planners, commercial managers and contract administrators. The increase in demand can be mainly attributed to tighter project durations and budget restrictions. Unfortunately these demands do not result in any sympathy for contractors and should they incur any delays or additional costs it, it is their responsibility to demonstrate this. The data regularly captured and archived in any software will always be valid, irrespective of the software as the software can only interpret that which it is given and should this not be accurate the outcome will also not be accurate. Hard facts will always be needed to demonstrate any entitlement, irrespective of the software used. Therefore contractors will have to seriously consider the hard facts before going to software! Stefan Müller is managing director of GibConsult, specialist in contract and claims administration.

By Annette Muller

•

June 8, 2021

Construction projects, like holidays, require planning and preparation to be carried out early enough. Accordingly, costs will be lower and it will allow for a more proactive schedule needing fewer constant changes L ooking back at the past holiday season, a very interesting observation can be made. Many begin to plan their holiday as early as possible, with some holidaymakers even booking the same accommodation for the next year’s holiday season before departing. Others will begin planning around June/July for the year-end. A small group of holidaymakers will leave it until November/early December and then rush around trying to find suitable accommodation, amazed that their choices are limited. This compares to the last-minute pressure starts that seem to be the order of the day. Much the same as the last-minute traveller who leaves straight after work and drives the entire distance with only fuel stops, arriving with the family ‘gatvol’ (meaning, fed up). This family is already preparing for the long slog back home with some trepidation, and will not unwind and enjoy the holiday as much as the well-planned holidaymakers. Groundwork In preparing for a holiday, a destination is sought that would cater for the requirements of the family, be it for an active holiday or the relaxing type. Activities are planned daily, including some alternatives should the weather not be conducive to specific activities. In the construction industry, a project will have (or should have) a detailed scope of work, which requires the contractor to then draft a planning schedule to demonstrate to the client that the work can be completed within a certain time frame. However, things will not always go as planned, so the contractor allows for spare time — known as a float — to be included in the schedule. In the Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation (2015), a significant factor identified for the success of a project is when more communication takes place between the various stakeholders during the scoping stage, compared to unsuccessful projects where less time is spent on scoping than on execution. Although this survey applied to the oil and gas industry, there is no reason to doubt a similar outcome in the construction industry. Therefore, if you know the destination, it becomes more manageable to plan the journey — this would also apply to the construction industry. Knowing the exact scope would allow the contractor to plan and price the work with greater accuracy. Implementation Travelling to a holiday destination with children, one question is always asked, ‘’How far do we still have to go?” This question is a result of the children not actually knowing the travel time and distance, as they were not shown a detailed travel plan indicating fuel stops, food breaks, and overnight stops. If they had more details of the travel plan, they could have looked out of the window and determined how far they still need to travel. The same applies to construction projects where the journey does not seem to follow the planned schedule as new activities and scope keep popping up. This may be the result of another issue identified in the abovementioned journal, where successful projects have a large number of stakeholders engaged in project scoping, whereas unsuccessful projects restrict the number of team members to be involved in the scoping of a project. Prudence Certain holidaymakers will arrive rested and relaxed, because the journey was well planned and communicated within the group, compared to the last-minute holidaymakers who paid a premium for making last-minute plans and were basically forced to accept what was offered. Construction projects are very similar. The better prepared and planned projects will inevitably also be the more successful projects. Therefore, it would be prudent to determine exactly what the client expects before signing a contract. Also, include all stakeholders so that as many risks as possible can be identified and addressed during the discussions that take place before contracts are signed. Once the contract has been signed, the unpleasantness of attempting to find an amicable solution for work that was not envisaged or was not interpreted correctly becomes an issue, resulting in the souring of relationships, which could have been avoided. Let us strive for more relaxed, well-communicated and successful projects for all in 2017. Stefan Müller is the managing director of GibConsult and a member of the Institute of Construction Claims Practitioners (MICCP).

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

The risks in having construction claims recognised and accepted can be substantially reduced through proactive contract administration, whereby reliable records and documentation are generated as the event occurs. In modern-day team sports such as cricket and rugby, we have an on-the-pitch umpire or referee, or as in the case of cricket, two umpires. It is expected of the umpires to make on-field decisions regarding events that occur on the pitch in a fair and just manner. However, due to the complexities during the event, it is not always possible for the umpire to make a fair and just decision on the event and he will then refer to the so-called television referee. The television referee will study all the available information recorded in both slow motion and real time to make a fair and just decision. The same situation occurs on construction projects when claims for both time and money are being submitted for a fair and just decision by the client. The contractor learns that the claims submitted are being scrutinised in the finest detail to either reject or to minimise the settlement value of the claim. The information available to the television referee will come from strategically placed cameras and camera operators. Should one of the strategic cameras have been unable to record the event, then the decision will be based on the available information and will probably not be to the satisfaction of both players and fans. The television referee or an arbitrator make their decisions based solely on the facts reflected in either the film recording in the case of the television referee, or from the detailed documents submitted by the contractor in the case of the construction claims. It is therefore understood that it is vital to submit all relevant documents when submitting a claim. The risks experienced by most contractors in having claims recognised and accepted can be substantially reduced through proactive contract administration, whereby reliable records and documentation are generated as the event occurs. Preparing the claim In preparing his or her claim, the contractor will correlate all information pertinent in support of the claim, whether it be for an extension of time and/or money. As with the television referee, the event leading to the claim to be drafted has passed. Thus, only the recorded information in the form of correspondence, site daily diaries, technical reports, drawings, time schedules, and drawings can be used to assess any entitlement. In addition, any costs also need to be substantiated and here copies of invoices, payments, lease and/or rental agreements, salaries and wages, and so forth must be supplied, to clearly demonstrate the costs that have been incurred because of said event. Assessment The contractor will submit the claim, with supporting information and documentation, to the responsible client representative on site who, as in the case of the match official, will either accept or reject the claim and hopefully give sufficient reason for the decision. The contractor and client representative will exchange views and documentation in an attempt to resolve the issue. They will, however, reach a point where both parties can no longer convince the other to their point of view. With a stalemate being reached, a dispute would be declared. A final attempt to reach some kind of amicable solution will also be made by the responsible leaders of the parties. Should this also fail, then the matter will be referred. When considering all the documentation available at this stage, one may believe a dispute could have been avoided had a notice or letter been submitted or more effectively communicated. A contractor who demonstrates a regular and proactive approach in submitting notices and/ or correspondence is less likely to end in dispute. However, when a dispute cannot be avoided despite good communication, the habit of providing the correct notices and correspondence in a regular fashion is more likely to achieve a fair settlement with the dispute process. Referral Having declared a dispute, the issue then is no longer under the control of the persons on site, but is referred to a neutral third party. The contract agreement will describe the procedure to be followed where a dispute is declared. As in the case of the sporting event, the contractor can be convinced that the right decision was not made and request that an independent person in the form of a mediator or an arbitrator review the claim. The role of the mediator is less independent because the mediator will work closely with both parties in trying to find a solution to the dispute. A contractor who demonstrates a regular and proactive approach in submitting notices and/or correspondence is less likely to end in dispute. As in the case of the television referee, the arbitrator or mediator will request all supporting documentation relating to the event. In the case of complex issues, interviews may be carried out, expert witnesses called in, and so on. The arbitrator will scrutinise the documents and arguments delivered by the parties in an attempt to understand the issues and to then reach a fair and equitable decision. Conclusion The awareness of the contract administrator is paramount in avoiding potential conflicts and risks. Risks should be identified as potential claims and be addressed in an amicable way before emotions are brought into the decision-making process. As with the television referee, any decision made where all the facts are well presented, with no malfunctioning camera, all parties will accept the decision and continue to work together. It is only when one party feels aggrieved that events become unpleasant and tend to end up in a long and costly process to determine the legitimacy of any claim.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

T he escalating costs of many large infrastructure projects could be mitigated by adopting a simpler approach to root out the causes of cost overruns, preventing them from impacting negatively on the project, says large infrastructure claims and contract administration company GibConsult. GibConsult MD Stefan Müller questions whether large-scale projects are realistic or, perhaps, too ambitious, highlighting a particular German infrastructure project as an example of a project with significant cost overruns. The country’s toll-collection system for trucks had a cost overrun of €6.9-billion, which equated to a cost increase of 1 150%, compared with the original cost projection. “Locally, the Gautrain project indicated a R20-billion overrun, and [State-owned power utility Eskom’s] Medupi and Kusile power station projects are estimated to have collectively overrun budget by about R80billion,” says Müller. He cites a study, titled ‘Large Infrastructure Projects in Germany – Between Ambition and Realities’, conducted by the Hertie School of Governance, in Germany, and published in May, which indicates that, of 170 large construction projects undertaken in Germany from 1969 to 2014 – with 119 having been completed and 51 still in progress – the combined average cost overrun for traffic (road/rail) and public buildings was found to be 33% and 44% respectively. Müller, however, notes that the cost overrun challenge is not unique to Germany or South Africa, nor to large infrastructure projects, although large infrastructure projects have the greatest negative impact, owing to the significant complexities of the projects. “With large-scale projects, extreme cost increases are placing contractors and employers in risky situations when new challenges arise,” he adds. Reviewing the Original Budget The first solution to mitigate a looming cost overrun is to review the original budget as tendered, notes Müller. “There are a few strategic considerations that are identified as low-risk issues, and these are normally ‘hidden’ in the contract documents,” he says. A good example of this is submitting the project or baseline schedule to the employer, he highlights, adding that the importance of this schedule is often not recognised or considered, owing to lengthy project durations. He states that potential delay entitlement will be measured against such a schedule, as well as any errors in timeframes or agreed milestone dates. “Contracts, in general, request a project schedule within 30 days of [the parties] having signed the contract,” says Müller. However, it is often difficult to submit an accurate project schedule at an early stage of a project because of the lack of auxiliary contracts signed by equipment suppliers and manufacturers. The contractors can, therefore, only submit their intended schedule, he explains. “This becomes a risk factor when milestone dates are enforced on potential suppliers and manufacturers who might be desperate to accept such contracts.” Clear Scope Definition The second step to mitigating cost overruns would be to define a clear definition of the scope of work, highlighting what is included and what is excluded from the scope. A clear and concise definition is required to calculate a fair price for the work, states Müller, adding that unknown pricing quantities can be “a bit of a lottery in today’s market”. He adds that, although the contractor might agree to accept full contractual responsibility for the design and functionality of a project, “the customer almost always wishes to imprint his or her ideas on the design, with a potential cost impact on the contractor.” Contract Administration Müller notes that contract administration is also an important budget issue. “On average, all projects have a claim potential of about 20%, of which 50% are recognised too late or not at all,” he says, adding that experienced project managers, project engineers and commercial managers battle bravely with “one arm bound behind them”, suggesting that project managers have limited capacities in terms of unforeseen issues that arise. Müller explains that a trend is for the technical or engineering issues of a project to be handled as they occur. However, issues can arise, owing to the project schedule not necessarily being used as a guide for upcoming activities, and procurement not being kept up to date on progress and potential changes to the original schedule. Further, claims for changes to specifications in design and on-site delays require urgent attention and should be identified and dealt with, as early-warning notices and communication with relevant parties are promoted. He says that, unfortunately, in most cases, even when management feels issues are being dealt with rapidly, they are actually taking too long to deal with the issues. Müller notes that, from his experience, any reasonably sized project in Europe will have a dedicated contract administrator on site and another at head office. “The on-site contract administrator will identify and record potential claims events. This information will then be forwarded to the head office contract administrator, who is responsible for the preparation and packaging of the claims being submitted to the customer,” he explains. Müller adds that gathering details, documents, costs and correlations must be done in a competent and professional manner to acquire maximum entitlement for any claim events. “It may be convenient to depend on inexperienced resources and software, owing to complacence which is negated by fixed periodical reports and audits by a third party; however, whatever is archived will become the basis for any entitlement to a claim and, should that basis be inadequate, this will weaken the claim and might even result in a complete rejection of the claim,” he notes. Larger construction companies have mostly identified and accepted this way of operating, says Müller, adding that smaller companies, however, still consider a “handshake” as contractually binding. Interview with Stefan Müller by Dylan Slater | CREAMER MEDIA WRITER

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

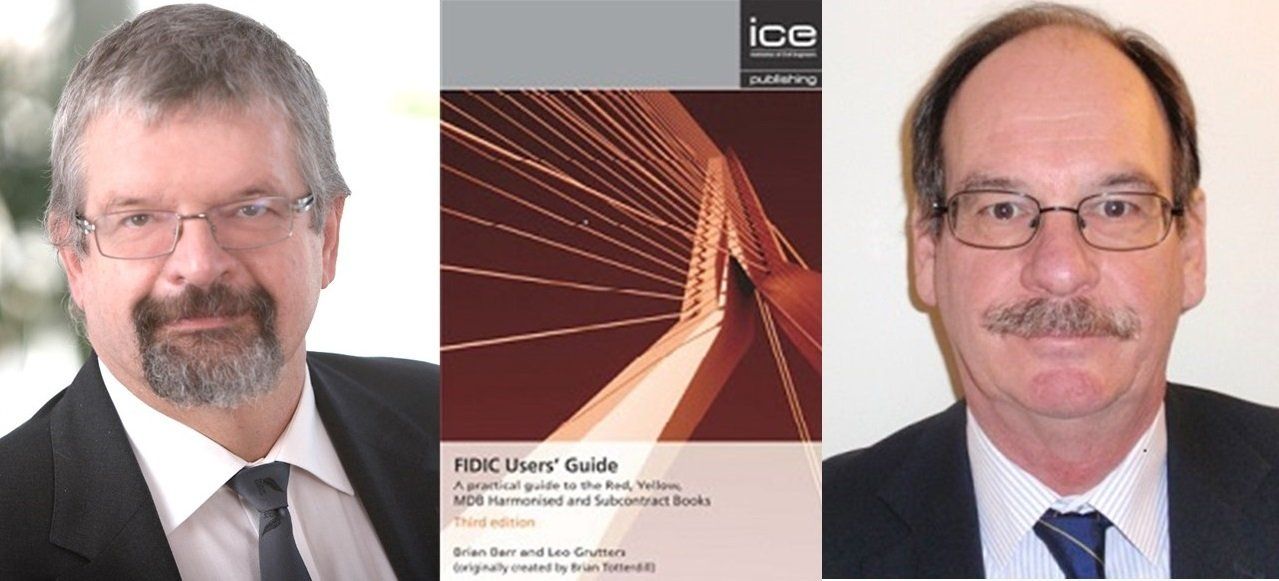

Professional insights and practical solutions for the more controversial issues when dealing with FIDIC contracts . The FIDIC Users´Guide 3rd Edition has been launched in South Africa. The third comprehensively revised edition of the world-renowned Brian Totterdill’s FIDIC Users´ Guide is a must have reference guide for construction engineers, construction lawyers, contract managers, contractors, claims specialists developers, quantity surveyors and local authorities - everyone dealing with FIDIC contracts. At a media conference in Centurion the media were given insights into the new FIDIC Users´ Guide from the authors. The viewpoint from the contractors and sub-contractors was presented by Wayne Derksen, President of the Lephalale Chamber of Commerce. Brian Barr, of Brian Barr Consulting Services in the UK, and Leo Grutters, co-founder of GibConsult, the sponsor that brought the authors here, have more than 40 years’ in-depth FIDIC experience. Both are members of the exclusive FIDIC President’s List of Approved Dispute Adjudicators – there are only 59 worldwide. Not only does this 1, 6 kg publication stimulate better contract administration, it highlights accountability and addresses contentious issues with relevant conclusions on dispute avoidance rather than dispute resolution. The authors took into account newly published forms of contract, case studies, the increased use of the 1999 FIDIC conditions of contract on construction projects into a more international arena, and incorporated the current industry’s thinking and understanding of the FIDIC terms and conditions, making the book an all-encompassing volume for readers. The proper use of these standard forms of contract significantly reduces the inherent risks contained within development projects. Clear advice to practitioners on how to mitigate and avoid contractual problems, are provided. Leo Grutters, co-founder of GibConsult, explains, “Over the years it became even clearer that the day to-day users of FIDIC forms of contract were trapped within the complexity of these forms of contract. This stems from predominantly a significant interlinking of the various sub-clauses. The need for clarity and transparency was established and the book aims at providing this for all users legally trained or not.” Dr Cyril Chern, from the Dispute Board Federation, stated, “This work of reference brings professional insights into and practical solutions for the more contentious and controversial issues when dealing with FIDIC contracts.” A one-day workshop was held in Midrand, in March 2014 where delegates were shown how to deal with the FIDIC Users’ Guide from a practical use requirement. The learning included the often unknown or misunderstood pitfalls when using FIDIC contracts, the contract administrative burden when using these contracts, how to correctly interpret some of the more complex issues in FIDIC contracts. Furthermore, it provides a Reference Guide to be used during a construction project for construction engineers, construction lawyers, construction claims specialists, contractors, developers, quantity surveyors, local authorities and everybody involved in or will be involved in a construction project using or contemplating using FIDIC. The South African Institution of Civil Engineering (SAICE) and Consulting Engineers SA (CESA) support the GibConsult South Africa initiative to bring these renowned specialists and co-authors to South Africa for the benefit of their members and the broader contingent that was already mentioned. The third edition of the FIDIC Users’ Guide is essential reading and is available from the SAICE bookshop and can be ordered online at www.saice.org.za/book-store

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

The philosophy of disputing the need to dispute is based on the implementation of professional contract administration preferably introduced at the tender stage of any construction project. By Stefan Müller. In a recent survey by the Chartered Institute of Builders, Managing the Risk of Delayed Completion in the 21st Century, it was found that” the more complex the project, the less likely it is that it will be completed either on time or shortly after the completion date, using the traditional management methods.” Experience also shows that settling in claim associated with delays and additional cost, invariably becomes a long drawn-out and problematic affair when kept records are poor or non-existent. The newly published FIDIC Users’ Guide 3rd Edition, from authors Brian Barr and Leo Grutters, also emphasizes the use of the practical administration of the various forms of FIDIC contract. It would not be amiss to recognize that any form of contacts requires some form of administration applied will impact directly on the level of success in identifying and addressing the risks and chances inherent in any given project. This is also supported by the following quote from Swiss Arbitrator (1996) who stated that “A party to a dispute particularly if there is arbitration, will learn three lessons (often too late): • the importance of records, • the importance of records, and • the importance of records.” Minimising impacts In introducing a more professional contract administration approach to minimize the impact of delays and risks of additional costs, the need to incorporate the following phases of development within a project or company is required: • contract risk and chance analysis, • site workshops and audits, • claims identification and preparation, and • claims negotiation. Following these phases will result in achieving an optimal entitlement and where a party is not willing to consider an amicable agreement, the administrator would serve as the basis for preparing any dispute process. A contract must be fully understood by both parties to enable the parties to assess the associated risks and also chances when pricing such a contract for budget or tender. Risks are not always evident at the tender or even kick-off stage of a project. Only during the execution phase will the inherent risks or chances become evident, if it is understood that a contract is drafted to clearly define the scope of work and the payment of such work. Secondly, should any deviation or change occur to that which has been contractually agreed then the contract should describe the procedure to be followed in dealing with any such event. The procedures are to be strictly followed in order to secure any entitlements resulting from any change. The procedures, however, are often interpreted differently by the parties to the contract and can then result in a complete or partial loss of entitlement. “ A contract must be fully understood by both parties to enable the parties to assess the associate risks .” Reasonable Time Interpretation or definition of a contract phrase such as “reasonable Time” or” available” can be easily identified during a risk and chance analysis to assess the potential risk with the following clause “… The purchaser shall within a reasonable time provide the contractor with all available design parameters need for the execution of the project…” These commonly used types of phrases or words can be easily misinterpreted as there is no clear definition of understanding of “reasonable time” and or for the word “available” which could be anything or even nothing. In the instance where the employer, for example, supplies the design date the following typical contractor clause would not be uncommon;…”The contractor shall be reasonable for verifying and interpreting all such data. The employer shall have no responsibility for the accuracy, sufficiency or completeness of such data… ”here the risk is being transferred to the contractor who would be required to clearly demonstrate that the data reviewed was incorrectly or false and that at the time of receiving this data the contractor was not in the position to verify the validity of the data. If the contractor incurs additional costs and time, this would also have to be proven and substantiated. Different interpretations Generally during the initial negotiation stages, all parties tend to be very optimistic about the viability of the contract which is generally based on each party`s interpretation of the work to be done. This situation tends to dramatically change once the actual work starts as the practical implementation of the contract requirements may not then be as clear as originally envisaged. Once the project actually commences with the implementation phase the introduction of a professional contract administration becomes a valuable asset to any project management team. The contract administration will ensure that the quality of records required to support any entitlement is enhanced by the scope of the relevant, contemporary records submitted. In addition, the timely registration of identified claims will serve to ensure the opportunity to collect and compile all feasible proof. Thus, the identification of possible “grey areas” within contract documents must be undertaken in order to assist in clarifying these issues with the potential employer and if need attaching a commercial value to identified risk. Stefan Müller is managing director of GibConsult South Africa.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

After assessing the contract risks and chances during the tender and negotiation stages, the next stage would entail the implementing of professional contract administration. The first step would be to sensitise the construction project team. By Stefan Müller . Having signed the new contract does not necessarily mean that the project objectives have now been secured. In particular infrastructure projects, such as power stations, are subject to a tremendous number of interface problems and unforeseen circumstances that arise during the course of the project execution which would be difficult to sufficiently forecast in order to facilitate a provision in the contract for the specifically identified event in advance. This is where the employer normally incorporates “lessons learnt” from previous projects into new contracts. There is no reason why the contractor should assess potential risks from previous projects in the same manner and possibly include a cost allowance when tendering. Nuances matters The prerequisite for a common understanding of the requirements of the newly signed contract between the tender negotiation team and project execution team becomes very important. The understanding of the nuances and interpretations of the contract by the tender negotiation Team needs to be communicated to the project execution team. This communication is also to include details of the contract price as this relates to the budget constraints that will be placed on the project execution team. Often the actual scope of works includes the term “fit for purposes” within the technical requirements. This term loosely means that once completed the constructed will perform to the expectations of the client as he has envisaged. This may not be the same performance that the contractor has understood or even delivered. Investigate and Identify Recognising the inherent risk involved makes it even more important that more time is spent in the early stages of the project on investigating and identifying possible risk areas. A common misconception that may explain this is that a project that has been procured at a loss or below budget can be “saved” by submitting claims to provide or bolster a profit margin. This, however, is very difficult if not impossible, as any claim submitted by the contractor will firstly have to be proven not to have been included within his scope of works and secondly the commercial or cost impact will have to be proven. Proving additional costs require substantiation that the cost has actually been incurred, for example, money having actually been spent. That would mean that the contractor has spent money which he would have to defend and now has to try and recover the costs. This in essence means that parts of the project is then effectively being pre-financed by the contractor. Tender team Discussions between the tender team and the project execution team would have to be open and honest. Identified risks and chances need to be discussed and this could also result in further discussions with the employer. In acting professionally whereby the employer is made aware of potential unforeseen costs, the contractor enables the employer to be proactive and the employer can then decide, prior to any additional costs being incurred, whether the employer is in agreement or even if an alternative, more cost effective solution can be found between the parties. Although dispute boards are a less costly exercise than arbitration there still are significant associated costs without consideration to the effect on the contractors cash flow, where claims or even variations are being disputed and cost have been already incurred. Dealing with claims for additional work and costs therefore need to be dealt with in a timeous manner to minimise the impact on the project finances. This can only be done if the project team is well informed and when the contract administration is effective and up-to-date. Site Workshops and Audits and what this entails is the next phase for the successful execution of a project executed with preventative contract administration.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

The foundation to establish good communication and understanding between parties starts with site workshops and audits. The parties to a contract develop a beneficial relationship if communication between the parties is open, honest and properly recorded. This article discusses Site Workshops and Audits, the next phase in the successful execution of a project executed with preventative contract administration. By Stefan Müller Commencing site or construction activities now follows all the procedures included in the preparation phase as described in the previous articles. Once the project team has been established an intensive one or two day workshop, depending on the size of the project, should be arranged. The goal of the workshop is to take the information gathered by the tender team together with the analysis of the contract and exchange this knowledge with the project team. This enables the project team to have a clear understanding what is to be done and, importantly, why. This information enables the project team to be fully aware of the identified risks and chances generated by the project. Often projects are run based on the previous project without any noticeable improvement as the apparent risks have been calculated into the tender price. Only if the complete project team is made aware of the contract conditions can they be expected to be able to pre-empt certain risks and or identify chances timeously. Our experience and knowledge is available to facilitate the contract analysis, present and moderate the workshop. The kick-off meeting with the client should also be used to clarify certain practical issues that normally lead to unpleasant surprises in the latter stages of the project. This would be issues such as the format of any claim document and the level of substantiation of costs, methodology of demonstrating and extension of time entitlement, etc. Open and honest communication between the parties is a must for the success of any project. Changes in design One would assume that the actual work can now be started on the project. However, the first issues can arise at this point. Either the site access cannot be granted or the contractor has not completely mobilised his project team and therefore in the eyes of the client not ready to start. This becomes very interesting when both events occur simultaneously. This does happen more often than one would expect. Further issues then start arising during the “design phase” as it is very rare that the design used during the tender would be identical to that which is actually being built. Anyone having built a house will know that that which they envisaged at outset is different to the house of which occupancy is taken. The difference and changes in design would be very quickly identified and with a good builder, costs would be discussed and agreed before the changes would be carried out. The only difference to larger infrastructure projects would be the amount and complexities of such changes. In addition the issue of who would be responsible for initiating the changes also requires clarification as this would determine which party would be responsible for the time costs impacts of any such change. As with building a house the agreement on who is responsible for the time and costs must be determined before commencing with implementing the changes. I say must as this will normally also be stated in the contract documents. Cordial relationships However, in an effort to maintain cordial relationships with the client the contractor often decides to carry out the work on a verbal instruction to proceed given by the client and often without the client knowing what the actual costs would be. The contractor would happily incur costs in the believe, that all costs can be recovered and thus is not too concerned as to the amount spent and often not even recorded correctly or accurately. Also, budgetary constraints may not even be put in place by either party. The client might have estimated the costs for himself based on past experience and this estimation may be well below that which the contractor submits with his claim. At this point it would be clear to anyone that once the costs have been submitted to the client, the client will be surprised that the costs for the agreed changes are not what was expected or budgeted for. Thus, we now have a situation whereby the contractor has incurred costs which the client is now not in agreement with. How this situation is now handled, will give a good indication how the relationship between client and contractor will develop. On the contractor side, if all costs are well documented and clearly show, by means of drawings, technical documents etc. a fair assessment of the costs can be expected. The client, if accepts and is prepared to recognise and pay the assessed costs then we do have a good relationship developing. Any reduction in the claimed costs which is not well documented with factual arguments will be seen by the contractor as being unfair and therefore unjust. This would not be conversant with the development of a good relationship. At this point it would also be fair to state that a bad tender cannot be corrected by increasing claim values or quantity of claims. Bad tender or quote is understood to be under budget and is submitted as a way to acquire a project with the aim to recover costs during the construction phase. This is unfair and unjust which does not bode well for the contractor who considers such an approach. Therefore, all changes and or instructions are to be well recorded and documented. A clear and open communication between the parties is to be actively supported by the parties. Most importantly changes need to be either priced or agreed how the costs will be recorded, if the costs cannot be determined and will be ongoing over a long period then monthly incurred costs should be reported on a monthly basis. This must be done in writing before commencing with implementing any changes. When is the project completed? The next phase for the successful execution of a project executed with preventative contract administration will be discussed in the next issue of the Civil Engineering Contractor. Stefan Müller is managing director of GibConsult South Africa, specialist in all aspects of contract and claims management for clients in the construction, engineering and mining industries. www.gibconsult.com

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

Complete a project successfully by recognizing mistakes and addressing similar risks on new projects. As in any contract agreement, there is a clear and defined completion process to be followed to consider a project completed. This can in some instances be a very painful experience as contractors will consider that handing over the project and the commencement of commercial operation or occupation by the customer as having completed the project. Contracts normally state the conditions to be fulfilled to achieve completion. However, we need to address the issue of lessons learnt once contractual completion has been achieved. Committing the same errors a second time is considered by some to be the definition of insanity. Therefore, we consider reviewing the lessons learnt and incorporation these lessons into “proven” procedures as being the final phase for the successful execution of a project by adhering to the proven principles of preventative contract administration and reflecting the philosophy of Disputing the need to Dispute as practiced by GibConsult. Exchanging experience Key personnel will rotate between projects and normally carry an immense amount of experience of various projects which can be tapped into when doing a project. However, upon completion of the project they would already have their minds set on the new project. New projects tend to excite people and make them forget to share their valuable lessons with the various related project team members once a project is completed. Ideally a close-out workshop should take place with all project team members present where information and experiences are exchanged during the duration of the project. It is of utmost importance that the agreed lessons learnt by the project team are conveyed to the various decision makers and departments involved with acquisition of new projects, such as legal, commercial and contract administration. All lessons have been paid and in some cases very dearly; claims with values in excess of R1-million can be lost just by submitting a claim late. It is not unheard that this error will occur more than once in project companies. Then surely organising a one-day internal workshop to exchange information and experience would be money well spent. Unfortunately, this does not happen and identified risks which can be turned into chances are easily ignored. Ensuring total completion A project can only be seen as being successfully closed out if the technical and administrative activities have been completed within the agreed budget, and any additional work of delays have been adequately compensated. Any negotiation for compensation will clearly depend on the quality and details of supporting records and documents. The importance of records related to a compensation event cannot be over emphasized. These lessons are normally learnt only once the customer or employer rejects the contractors claim for compensation. The contractor then has two options namely to swallow the bitter pill and accept the rejection. Alternatively, the contractor can seek relief via the Dispute Adjudication Board (DAB) or arbitration. By Stefan Muller

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

By acting proactively and not just reacting when changes occur, it is possible to still be in control and to steer the project to success, writes Stefan Müller. “I have to change a lot of things before become a good marathon runner,' said I Haile Gebrselassie, the Ethiopian long-distance track and road runner who won the Berlin Marathon four times consecutively and also had three straight wins at the Dubai Marathon. The same approach could be applied to managing and executing an infrastructure project successfully. As in training for and then running a marathon, project management always comes with changes and deviations from the original plan. It is normal. By acting proactively and not just reacting when changes occur, it is possible to still be in control and to steer the project to success. To be able to run a marathon one would seek and gather as much information and details as possible before starting to train. Drafting a clearly defined training plan with distances and times allocated for each weekday activity with a rest day included in the programme is a good start. A log will be kept on distances and time taken for each activity and time will be compared with previous runs over the same distance and with the times of peers. A complete cycle from the preparation, the race and after race analysis of the positives and negatives and what should be kept and what should be changed in future prevents one from making the same mistakes again. Before submitting a tender proposal for an infrastructure project in the construction industry, as much information and details as possible are gathered. A clearly defined schedule plan with costs and times arc allocated for each activity with allowances for public and staff holidays included in the programme. A monthly programme will be kept recording progress and costs for each individual activity and time will be compared with project budget and maybe even compared with previous similar projects. Costs and time are hotly debated as to the pros and cons of the various method statements and technical advances which could be implemented. When entering a race the top athletes will compete for gold and silver. To receive these medals there is a pre-determined time allocation. In most projects the gold medal is believed to be achieved when the tender has been granted, however, in reality the gold medal will not be achieved as projected costs arc in most cases exceeded and time schedules hopelessly extended. Pre-mobilisation Pre-mobilisation preparation will include bond and bank guarantee submissions, long-lead items to be ordered. personnel resourcing, budgets and also the project baseline schedule is to be submitted before the project kick-off meeting. Projects begin with site establishment and continue in line with the project schedule and will hopefully end on the agreed project completion time. But the inherent risk of project delays is due to various reasons, some not necessary the fault of the contractor. These procedural provisions have been detailed in the contract agreement for such delays. A well-known example of projects running behind schedule and being postponed in our country are the Medupi and Kusile power plant projects. Many changes, delays and postponements are resulting in these projects being about four years behind schedule, not to mention at an immense cost. Compared to the current cost of both projects, the cost estimate of 2007 has now more than doubled. Were all the parties sufficiently prepared for such a huge infrastructure project? Even without hindsight t am sure that all parties would agree that the preparation and planning of the projects should have been better. Were any lessons learnt from the construction of the last power plant projects in the 1980s which were only commissioned towards the end of the 1990s? However, South Africa does not hold the patent to big projects going haywire. Olkiluoto 3, a nuclear power plant on Olkiluoto Island in the municipality of Eurajoki in western Finland. has similar delay issues. Construction began in 2005, and has suffered various delays resulting in the projected completion date being delayed several times from the 2009 target. According to the Financial Times in December 2014, construction of the Olkiluoto plant has descended into a farce. Recent estimates for completion are now 2018 with a calculated additional cost for completion of approximately several billion Euro. Unforeseen hurdles A typical example of unforeseen project delays In our country is strikes which influence not only the time schedule but could run into millions of costs incurred as a result of contractors having to continue paying wages and salaries without receiving any income for work progress on site. This applies to those companies whose staff were not part of the strike but where the site was closed for safety reasons and or intimidation which is very prevalent in our environment. The cause of any such strikes may not be influenced by smaller companies, however, the impact is definitely felt. Firstly in paying wages and salaries and secondly in attempting to recover these costs from employers who may also be suffering certain budget restraints leading to long drawn out negotiations and possible constant changing of the goal posts by their employers. In our experience the administration of any such entitlements is inevitably left until well after the event has ended and thus certain valuable procedural requirements have not been adhered to. The justification for such an entitlement then rests solely on the contractors belief that “everyone is aware that there was a strike event" or similar and therefore docs not have to prove the impact thereof and that tbc contractor only has to submit the costs and time lost. Fact is, the employer needs to be convinced "on paper" that there is any entitlement before considering any such claims. Staying on track Just as with running a marathon, one of the most pressing challenges is to keep the project on track. “On track" means maintaining progress in accordance with the schedule submitted within an agreed period after having signed the contract agreement commonly known as the baseline or contract schedule. The contractor is given a deadline to prepare such a baseline schedule - normally between one to three months. Consider that a schedule could have anything from twenty thousand activities which have to be included and may be used against the contractor by the employer a year or two into a project to disprove any delay entitlement or slow progress by the contractor. Then one begins to understand the difficulty in explaining why progress has not been in accordance with the schedule. This leads to the requirement for proportioning responsibility to a party for the delay or reason for not meeting the schedule. In preparing for delays and potential claims it is of the utmost importance to have dedicated contract and claims administration professionals installed in the project at the beginning in order to ensure that all contractual procedures are being adhered to. This in the long run will reduce the risk of following the dispute process in order to recover any time and money for unforeseen events. The post-project analysis is just as important in that every stage of the project is scrutinised. Lessons learnt can be included in future projects in order to achieve that potential gold medal. The gold medal brings in the project on time and within budget. Yes, there will be unforeseen events, however, if the contractor is in a good state of fitness challenges can be met and reduce the risk of losing any just entitlements. Stefan Müller is managing director GibConsult Photo: Haile Gebrselassie

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

The dispute process can be avoided in post cases by timeously submitting a detailed and accurate document, and a clear understanding by all parties to strictly adhere to the contractual procedures , writes Stefan Mueller. Normally when a contract is signed, there is just cause to break out the bubbly to celebrate: the client believes he has an experienced contractor to carry out the agreed scope of work, while the contractor who had just signed a significant contract for his business calculates a fair profit margin. It is during this champagne period that clients will attempt to offload additional risk to the contractor by requesting “small adjustments” that had been overseen, which would require a possible lengthy renegotiation and delay in commencement if the contract had to be amended. The contractor normally agrees to these “small amendments” although may not have considered the full risk. Procrastination strategy Fast forward to a stage in the project phase. The contractor has submitted his final claim for both an extension of time and associated costs for an event not of his fault. The contract would at this point state that the client or his representative would have to make a fair assessment of the claim and possibly even have to discuss the claim to fairly determine the value of entitlement in both time and money. If no settlement can be reached, the contract describes a dispute procedure to be followed in a further effort to reach settlement. The reaction from the client or his representative is normally an outright rejection, alternatively a request for further details. The request for further details will continue to a point to where the representative no longer has any option but to make his assessment. At this point, for unknown reasons on which we can only speculate, the representative is reassigned, and a new representative is introduced. The whole game recommences from the beginning as the new representative would like to make himself familiar with all the facts before making a decision. And does he get to make a decision? No, as he now finds himself in a predicament whereby he has incurred additional unforeseen costs and has used up a substantial portion of his cash flow as he was expecting to be fairly compensated within a reasonable time period for the additional costs. As this is now not the case, a trip to the bank in order to discuss an overdraft facility or a loan is required to maintain progress on site. But how long will the bank accept that a claim settlement is expected “any day now”. Realisation of contract procedures At this stage, the contractor may opt to consult with an outside party in an attempt to find a way to achieve an amicable settlement to the outstanding claim. This often results in this third party referring to the contract provisions in attempt to bring negotiations back in line with the agreed contractual procedures. This can be a huge challenge to the contractor as, having to work and maintain cordial relationships with the client and his representative, he now has to become adversarial in that the contractually agreed dispute process has to be followed to the letter to prevent any procedural errors which could jeopardise any entitlement. In my experience, this dispute process can be avoided in most cases by a detailed and accurate claim document submitted timeously, and a clear understanding by the parties of the intention by the contractor to strictly adhere to the contractual procedures in recovering that to which he is entitled. Within the confines of the contract agreement, the parties can still maintain a cordial and professional relationship. Not every year is a vintage As with champagne, not every project is guaranteed the envisaged profit margin or that it will be completed within the agreed duration. Thus, demonstrating a reasonable project schedule (baseline) which is followed within limits is a pre-requisite for demonstrating any delays not the fault of the contractor. Together with accurate detailed costs and manpower records submitted timeously, will “encourage” the client or representative to seek an amicable settlement to any claims. However, should this not be the case and the contractor has incurred certain costs or delays for which it can be shown by the client that the contractor is responsible, then surely if this is clear and understood early in the negotiations the contractor can and must proceed to mitigate his time and costs lost. The contractor and the client or representative have a similar obligation to demonstrate the fault of the contractor when dismissing or reducing any claimed amounts. For example, a general “but you were not ready to commence even if we had given you access”, is not an acceptable argument. Access to be given by the client is a contractual obligation at an agreed date which is stated in the contract. The date the contractor actually starts work is at his own risk as he has to then complete by the agreed completion date or face having to pay delay damages. This may sound simple and straightforward, and sometimes it just is. In starting the contract in a champagne mood, ending the contract can also be done in the same way if both parties follow the letter of the contract for the project’s duration. Stefan Mueller is managing director of GibConsult SA.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

Having processes in place will help guide the behaviour of the project team. A method is needed to ensure that potential risks and chances are timeously identified and addressed, writes Stefan Müller. In any successful team sport, once the event has been concluded, an in-depth analysis determines what was done correctly and, importantly, what went wrong – either to plan or to see what was successful. Based on this analysis, a game plan will be adapted and armed with a “new” strategy for the next event. This makes for a successful team and no costs will be spared to achieve the correct analysis and information upon which players will be chosen to implement the strategy. In complex infrastructure projects the game plan is no different. Basic strategy Companies choose the best manager to run their projects. The project managers, in turn, seek out the best engineers and supervisors to support their efforts in completing a given project. The definition of a successfully completed project may differ from company to company, based on the expectations at the beginning of the project. Success does not always relate to profit, as market share and maintaining market presence, to name a couple, may be just as important to the company. However, project losses may not necessarily be acceptable in any expectation. In choosing team members there are basically two types of members: those that follow instructions and those that are able to think outside the box to the advantage of the company. It is important that both types are evident in the team and the contributions made by both are equally appreciated. In the larger multinational companies where different departments or divisions may be involved in the same project, the issue of team playing becomes even more important. Considering that this should be easy, it often leads to one “defending” one’s position within the company structures, which can occasionally lead to “turf wars”, resulting in possible damage to the company. Thus, it is safe to assume that having processes in place will only help guide the behaviour of the project team. What is then needed is a method to ensure that potential risks and chances are timeously identified and addressed timeously. Prudent review In deploying an effective game plan for any project, it would be prudent to review past projects and even to analyse what worked well and what caused some hardship. Thus, it is important to draw on past experiences, which may be internal or even external in some instances. External sources allow for quick feedback, based on years of varied experiences and even with experience relevant to dealing with the exact issues at hand. Workshops should form part of any project preparation and it’s the perfect platform for all role players to openly convey their considerations and decisions made during the tender or proposal stages. A closing-out workshop would thus be just as important as a kick-off workshop. Having procedures in place will help guide individuals in the project team in dealing with specific events and the method (read game plan) will then determine exactly how to deal with the specific events. For example, in the instance of a labour strike where the construction has been closed down requires the contractor to follow the procedure set out in the contract agreement. This means submitting the relevant early warning notice, notice of claim and within a contractually defined time period, submit the claim document. Should the event continue for a longer period, then a monthly interim claim must be submitted. What is commonly misunderstood is that even though the contract may allow for additional costs for the event, the costs and time must be proven. It is at this point where the contract does not state which form or detail is to be submitted and invariably the document then is rejected for insufficient detail or proof. This lesson often leads to a negotiated settlement for time and costs below the expected values. Handshake agreements The construction industry should be aware by now that the age-old custom of ‘handshake’ agreements holds no sufficient assurance of an amicable agreement, as most decisions are seen to be made by people not necessarily involved in the day-to-day issues on a construction site. In essence, a multi-million rand claim would not be acceptable if submitted with a two- to three-page letter. It would require a multi-page statement of entitlement with numerous files containing the substantiation of costs, and must also include a project schedule clearly showing how planned activities were affected. The good news, though, is there are sufficient experienced managers out there to help with all facets of administration. Prudent operators will also frequently audit their processes and methods to assure project targets are maintained. It can be safely said that to achieve project success, the tools required for identifying risks and chances must be in place, and the necessary experience is as important when pursuing any entitlements. Stefan Müller is managing director of GibConsult, specialist in contract and claims administration.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

In the modern-era construction industry, contractual claims have become part and parcel of the day-to-day administrative duties of the project team. When contractual claims start arising, the understanding of the contract that was signed becomes the deciding factor in any claim entitlement, writes Stefan Müller The main reason for construction claims arising is seen to be initial budgeting, which is structured to be competitive, while also attempting to generate a small profit. Having achieved claims status, negotiations begin and further concessions are expected and, in some instances, demanded by the negotiators. When the alternatives offered make some sense, they result in cutbacks and deals being made in the heat of the moment. Considering that contractual/legal language could arguably be confusing to a layman, it is perhaps little wonder that consumer contracts have a cooling down period. However, as there is no cooling down period for construction contracts, it is assumed that all parties are equal and completely aware of what they are agreeing to. Once the project starts and claims start arising, that is when the understanding of the signed contract becomes the deciding factor in any claim entitlement. So how do claims vary and what has to be done to receive compensation for lost time and/or money? There is a saying in German, along the lines of: “Being right and getting your rights are two different issues.” This basically means that a contractor may have a legitimate claim, but the onus is still on the contractor to prove that he has a claim. The steps involved in pursuing any claims and the pitfalls associated with submitting them can be open to interpretation in some instances. The good news is the contract gives a clear indication of the procedures to be followed. Record claim histories If an event occurs where the contractor has a claim to an entitlement for either time and/or costs, all contractual procedures must be followed, with relevant notices submitted in accordance with contract provisions. It is a contractual requirement for a contractor to submit his claim within a specified time, failing which he may be time-barred if the contractual deadline has not been adhered to. One of the potential pitfalls is where a verbal agreement has been made to discuss the claim at a later stage, but this agreement then suffers from so-called “project amnesia”. In the preparation of the claim, all facts pertaining to the event should be recorded in chronological order, no matter how seemingly insignificant. These facts must then be incorporated into the claim document, clearly explaining why the contractor is convinced that he has a claim. Without any documentary support, it will be very difficult to demonstrate any entitlement. An example would a verbal agreement to prioritise certain activities, which could – in turn – delay other related activities. If the client is not made aware of any potential impact resulting from this agreement and written instruction is not received to proceed, it could result in the loss of any potential entitlement. As with the chronological history of a potential claim event, the documentary support of any additional costs incurred as a result of a claim must also be stringently prepared and submitted with the claim document. If the contractor cannot demonstrate a cost to the satisfaction of the client, the cost will not be recognised. Claim submittal The submittal of claims is where most contractors encounter difficulties. There are various reasons for a contractor to perhaps delay the submission of claims, ranging from not wanting to upset the client to only realising when a budget is exceeded that a claim needs to be submitted. Here are a few examples of the approximate claims made on some of the larger international projects: • OL3 Nuclear Power Plant (Finland) – EUR3.5-billion (R58.8-billion) • Panama Canal (Panama) – USD463-million (R6.83-billion) • Medupi & Kusile (RSA) – R50-billion Interestingly, it is not the actual amount, but that these figures have accrued over time, and in the case of OL3, the claim has proceeded all the way to arbitration for determination. In most cases, these claims become cumulative as they were not addressed by one or both of the parties timeously. Dealing with claims on a monthly basis, for example, may increase administration, but in the long run it is the most cost-effective route. Claim reality The hard reality is that if the contractor does not notify the client of potential claims timeously and receive clear written instruction or agreement of a change in the contract procedures, any entitlement will be jeopardised. The contractor, in acting within the procedures of the contract agreement, is acting professionally and in the spirit of the agreement. If the client chooses to operate outside of these procedures it must be recorded in some way. In no way should these procedures dilute the professional and friendly relationship between the client and contractor. Stefan Müller is the managing director of GibConsult, a specialist in contract and claims administration.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021

Project managers and directors no longer have the sole mandate to negotiate and settle construction claims. The contract agreement provides the exact procedure to follow in submitting claims for additional time and or payment. Projects owners include a contingency amount to absorb additional time and costs, however, the contractor must prepare and submit claims to receive any entitlements, writes Stefan Müller. In a recent construction survey, Climbing the Curve, 2015 Global Construction Project Owner’s Survey, published by KPMG, it was shown that “only 31% of all respondents’ projects came within 10% of budget in the past three years” and that “just 25% of projects came within 10% of their original deadlines in the past three years”. This means that 69% of projects are exposed to additional costs resulting from variations and claims. In addition, 90% of projects had their completion dates extended. Projects in South Africa do not differ from these figures. Why it is important to have claims paid on time? Contractors will be paid their normal monthly running costs, more commonly referred to as P&Gs, which is reflected in monthly progress payments. This, however, does not allow for any additional time and or costs. When contractors submit their contract price for consideration, it is normally a fine balancing act between income and expenditure. This balancing act is required to minimise the need for external financing, which normally comes at a premium. The financing costs would then need to be added to the contract price and this may mean the difference in actually acquiring the project work. Detailed, timeous claim submission The contract agreement will, in most cases, provide the procedure to be followed for submitting claims for additional time and/or payment. Failure to follow the correct procedures can lead to the rejection of the claim. Thus, it is important to track and record all costs associated with the potential claim event and also keep a record of the resources used in dealing with the claim event. Ignoring the correct procedures by only providing a short description or notice of the claim will certainly lead to rejection of the claim. If financing is required due to cash flow challenges, the claimed costs can be submitted if shown to be as a direct consequence of the claim event. The more efficient and detailed the record keeping of the claim events is, the more the risk of claim rejection is minimised. Only legitimate claims should be considered, as submitting claims with no contractual foundation of detailed support, will potentially have a negative impact on the relationship with the client. Once claims have been agreed and paid, the contractor can continue with business as normal. However, if claims cannot be agreed upon, additional costs will be incurred and additional financing may have to be sought. Financing institutions may need to be informed as the business/financing models do not reflect the stated income and expenditures and, without any communication, may cause a certain amount of nervousness among the lenders. The non-payment of claims can put enormous pressure on the resources of the contractor and should cash flow be restricted, it would affect the contractor’s ability to provide additional resources and materials. This may then lead to further delays for which the contractor would be held responsible. Unfortunately, it will then be very difficult to prove that delays to address issues of lack of resources or materials is a direct result of claims not being paid within the agreed time periods. Claim relief Claim relief is given by the client when he is satisfied that the contractor has submitted sufficient details to support any entitlement and sufficient funds are available. However, as performance bonuses are linked to keeping within the agreed budget, the client may procrastinate or refuse to settle claims. Claims will then be dealt with via the agreed dispute process where decisions made do not necessarily impact the agreed performance indicators of the project team. The moral dilemma facing the claims reviewer is whether to evaluate the claims based on merit or on the impact it will have on the budget constraints. The contractor does not have any influence on this evaluation and the only feasible avenue would, therefore, be for the contractor to pursue any claims timeously from the beginning of the project. This would require claims to be evaluated when funds are available and the inclination to pay them is more likely. The contractor can proceed with the work in a more efficient manner, which allows him the freedom to make decisions based on progress and time, rather than trying to concentrate on limiting losses based on a lack of available cash flow. The timeous settlement of claims benefits both parties as it enables the contractor to be paid for additional work, without weakening his financial base. This in turn strengthens the relationship with the client, who acquires a reliable contractor for any possible future projects based on a professional experienced relationship. All parties benefit, resulting in fairer and more equitable prices being paid for construction projects. Stefan Müller is managing director of GibConsult, a specialist in contract and claims administration.

By Annette Müller

•

May 20, 2021